KRISTIAN KRAGELUND

A Terminal Posture

Bjorn & Gundorph Gallery, Denmark

By Jeppe Ugelvig

Kristian Kragelund is a multi-disciplinar artist who's practice is concerned with how value and power asserts itself through acts of subliminal violence within the structural formations of every day life. With a particular interest in infrastructure and the built environment as a contested space of political, corporate and personal agency, and subsequently how the conceptual dynamics of production and consumption becomes determining factors of individual aspiration and contemporary identity.

Through a critical examination of commercial and industrial debris as ambivalent artefacts of the human condition in the 21st century, he proposes a reevaluation of the historical, material and textual inertia of the object, and its speculative potential as agents of a new sensibility; aesthetically applied as strategies of change and disruption.

Kristian Kragelund (1987, Denmark) received his BA (Honours) in Fine Art from Central Saint Martins in London and and MFA in Painting at Columbia University in New York City. He has exhibited widely both nationally and internationally and his work is held in several private and public collections including The Danish Arts Foundation and as a permanent public commission in Whitechapel, London.

An “artefact” is commonly defined as a historical object created by a human(oid) that provides information about the given time in which the object was created. Popularly employed by social sciences such as anthropology and ethnology, the term is noticeably vague in its definition: from a tool to a totem, it could be anything created by humans that gives information about the culture of its creator and users. In more recent times, the term ‘artefact’ has been introduced to describe a tangible by-product, or error, occurring as the result of the computation of data. The most common of these artefacts is a so-called “compression artefact,” a noticeable distortion of media (including images, audio, and video) caused by the application of lossy compression. These artefacts appear as spurious signals: visually, they appear as bands or ‘ghosts' near edges; audibly, they appear as sonic “echos.” In both cases, artefacts are carriers of complex information that has become partially or fully indecipherable–partially lost to history, unintelligible to human comprehension. But to which extent do data artefacts qualify as carriers of societal knowledge when their deteriorated language – broken data – goes beyond human semantics? What is the status of these new artefacts, as objects and as relics of their time – what “information” do they hold, as material or as objects in their own right?

In A Terminal Posture, Kragelund re-purposes a range of artefacts sourced from the data and energy industry into formal elements of artworks. A range of discarded full-size silicone discs (Untitled_Artefact_x, 2020), appropriated as rejects directly from a production site in Silicon Valley, CA., is installed throughout the gallery, their glitches particularly noticeable in the spectral colour patterns.

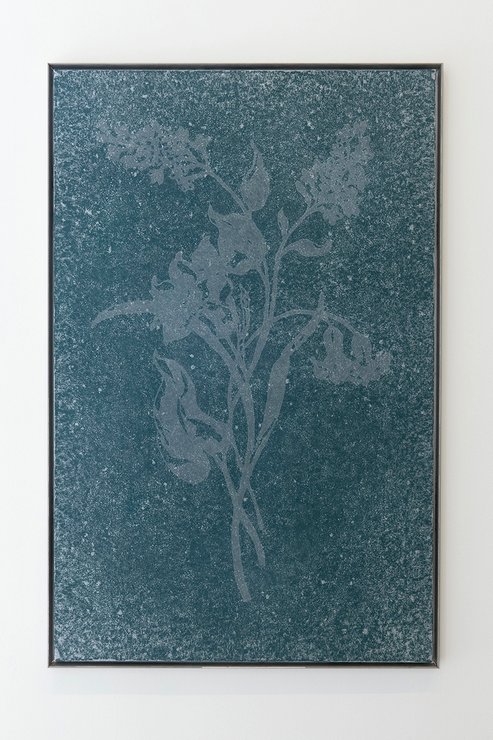

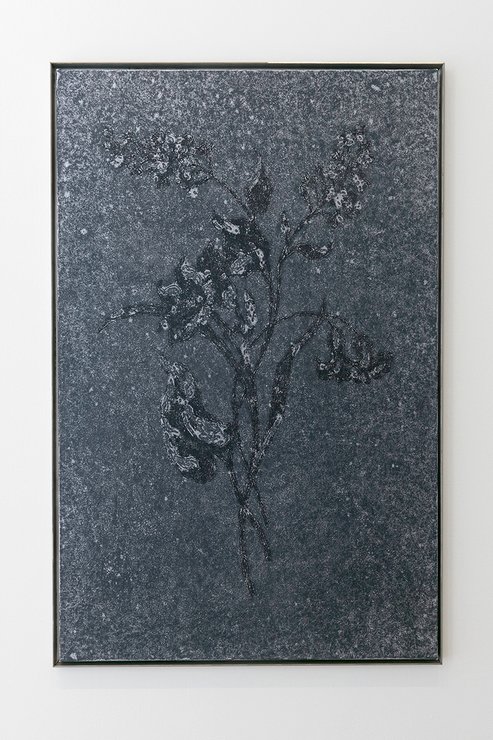

A new body of wall-based work (Untitled_Orchids 1-5, 2020) presents similar laser-cut silicon wafers – also known as semiconductors – sourced from a research facility in the US specialising in the development of automated control systems and artificial intelligence (AI) for the military industrial complex. Fitted within frames, these disused semiconductors can be considered as failed or burned out nervous systems of super-computers, once imprinted with data but now reduced to dysfunctional silicone relics: in other words, high-tech waste. Kragelund relates the unknowability of these former processes to his own prosopagnosia (“face blindness”) through the printed figure of an orchid, whose large genetic variety of colours and patterns makes it ideal for training face recognition to AI.

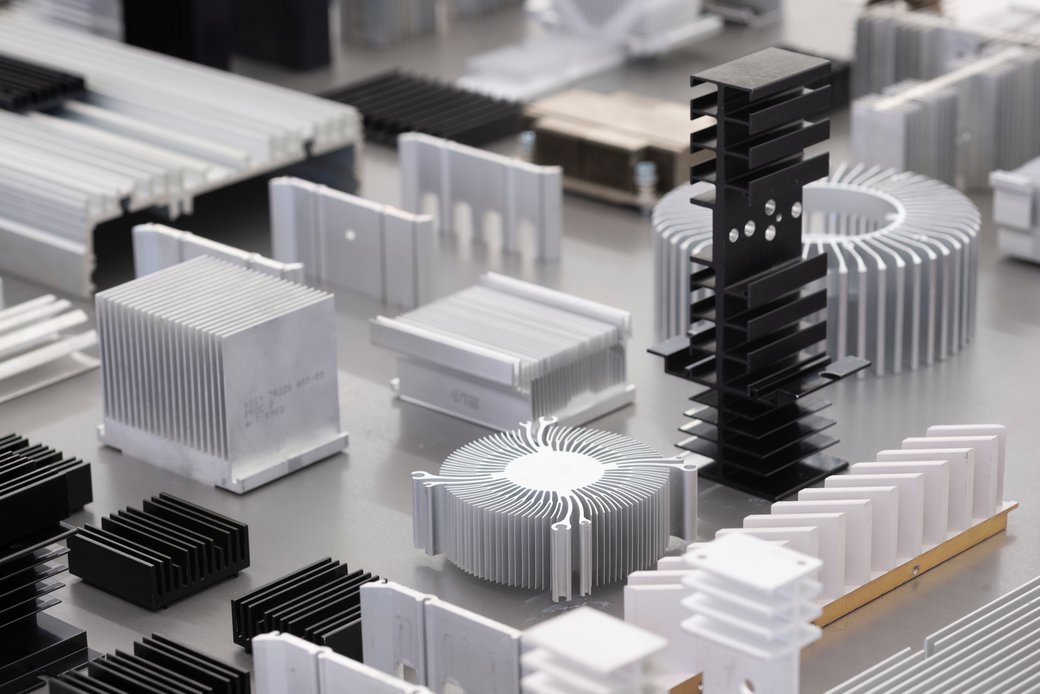

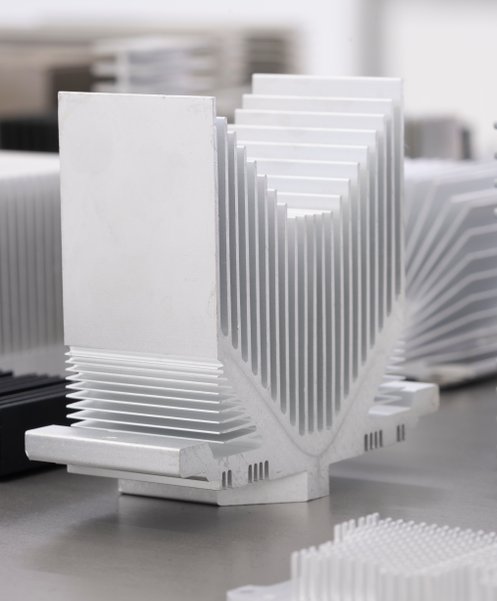

Elsewhere, arranged to an off-set grid-like pattern, anodised solar cells in blue technical hues have been stripped of their circuits and electrical wiring thus rendered unable to contain and distribute the energy the harvest (Untitled_CellF1, 2020). A sculptural work of reclaimed aluminium heat sinks from computer CPUs are organised on a horizontal plane resembling a model of a cityscape (Algopolis, 2020). Heat sinks are post-human design objects shaped by algorithms to maximise surface areas so as to expel maximum heat from computers; however, their formal resemblance to modernist architectural schemes suggests a deeper linkage between human and machine thinking around design, efficiency, and spatial administration.

The title of the exhibition is adapted from a particular short chapter in J.G. Ballard’s seminal novel The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), in which the boundaries of the mechanic and the human, the building and the body, poetically dissolve into impermanent placeholders and metaphors for one another.

“A TERMINAL POSTURE.

Lying on the worn concrete of the gunnery aisles, he assumed the postures of the film actress, assuaging his past dreams and anxieties in the dune-like fragments of her body.”

- J.G. Ballard / The Atrocity Exhibition, 1970

Through these various formal propositions, Kragelund offers a subtle critique and reading of the contemporary technological moment as it relates to creation and cognition – by humans and machines alike. By employing aesthetics in this process, he evokes its long critical tradition of grabbling with the most abstract of concepts: representation, information, memory, nature, time. His methodology suggests that while technology may already have exceeded or imploded many of these notions from within (often far beyond human comprehension), art still offers analogies – metaphors – to critically approach them, as entry points into deeper philosophical and political speculation.

Untitled_Orchids1-4, 2020

Expired and laser cut silicon semiconductor wafers, UV printed and mounted in artist frame

120 x 80 cm each

Algopolis, 2020

Reclaimed heat sinks on welded steel table

100 x 200 x 115 cm

Algopolis, 2020

Reclaimed heat sinks on welded steel table

100 x 200 x 115 cm

Untitled_CellF1, 2020

Malfunctioned and anodised solar cells in welded steel frame

200 x 200 cm

Untitled_Orchids4-5, 2020

Expired and laser cut silicon semiconductor wafers,

UV printed and mounted in artist frame

120 x 80 cm each

Untitled_Orchids4-5, 2020

Expired and laser cut silicon semiconductor wafers, UV printed and mounted in artist frame

120 x 80 cm each

Prosopagnosia

Untitled_Orchid1-5 is a series of laser-cut and UV printed silicon semiconductor wafers sourced from a research facility in the US specialising in the development of automated control systems and AI based facial recognitions software primarily for the military industrial complex. Mounted on aluminium and fitted within welded frames, these specific expired semiconductors can be considered as the failed or burned-out nervous systems used in the fabrication of super-computers. Once regulating the flow of energy and large quantities of sensitive data but now reduced to dysfunctional silicone relics.

On the surface of each of the five works are rendered illustrations of synthetic orchids - synthetic flowers are not based on an actual existing flower, they are designed and conceived based on the idea of a flower - thus addressing conventional notions of the still life and the reproduction of nature.

The flowers of (real) orchids are increasingly applied in the AI processes involved in developing facial recognition software, partly due to their large genetic variety of colours and forms, and partly due to recently introduced data-protection legislation restricting the access for private contractors to governmental databases. Orchids evolves much in the same generational manner as humans; the ‘offspring’ of an orchids might look somewhat different than the parental plant, but its genealogy can be traced via. geometrical scan in similar ways as a human face, therefore making them a valuable asset in computer-learning.

This relates directly to Kragelund’s own condition of recently diagnosed prosopagnosia (face blindness), and the existential questions that arises from the paradox of him being unable to recognise faces, whereas the software developed by means of these semiconductors and the imagery printed onto them, is capable of just that.

Untitled_Orchids1, 2020

Expired and laser cut silicon semiconductor wafers, UV printed and mounted in artist frame

120 x 80 cm

Untitled_Orchids2-4, 2020

Expired and laser cut silicon semiconductor wafers, UV printed and mounted in artist frame

120 x 80 cm each

Untitled_Orchids2-3, 2020

Expired and laser cut silicon semiconductor wafers, UV printed and mounted in artist frame

120 x 80 cm each

Algopolis, 2020

Reclaimed heat sinks on welded steel table

100 x 200 x 115 cm

Artefacts and The Age of Anxiety

Anthropologists have suggested that for analytical purposes, ‘culture’ can be viewed as a three-part structure composed of the following subsystems: ‘Artefacts’, ‘Mentifacts’ and ‘Sociofacts’.

An ‘Artefact’ is commonly defined as a historical object created by a human(oid), that provides information about the given time in which the object was created. More specifically it is a term used in the social sciences, particularly anthropology, ethnology and sociology for anything created by humans which gives information about the culture of its creator and users. However, from a philosophical point of view, the classification of an artefact is rather vague and relative.

Take, as an example a seashell used by indigenous people to scrape fat and tissue of the pelt from a skinned animal. Does the essential properties of an inanimate object change the second a human handles it and thus ascribes its function? Is it when the same human sharpens the edges of the seashell to improve the objects functionality, or is when the human picks up the shell from the riverbed and walks to the tannery station in her camp? At what point does the seashell become an artefact encoded with anthropological information and contemporary scientific relevance? A ‘Mentifact’ is a term used to describe the traits of a specific culture, such as beliefs, values and ideas. Furthermore, it offers classifications as to how speech, language and symbols over time have the potential to become conceivable objects in their own right. Mythologies, religion, philosophy, and folk wisdom are fundamental in this abstract ideological subsystem, inasmuch as they tell us what we ought to believe, what we should value and how we ought to act based upon those values and beliefs. This concept has been useful to anthropologists in refining the definition of culture. The idea of the mentifact was first introduced during the cognitive revolution in the social sciences on the 1960s, as a quantitative tool to grasp the complexities of cultures. Essentially, it disregards or at least questions the value of artefacts as defining elements of social epistemological knowledge, and proposes that cultural dynamics are created through a cineplex web of social interactions.

‘Sociofacts’, also known as ‘Psychofacts’, define the social organisation of culture and is applied to identify patterns of social relations (power structures), most notably in regards of a given society’s predominant political, military or religious affiliation. Sociofacts regulate how the individual functions relative to a group, whether it be family, church or state, and traces whichever behavioural patterns (i.e. rituals) are absorbed and transmitted from one generation to the next.

Of the aforementioned subsystems, the significance of the ‘Artefact’ for the way in which we structure historical narrative is the easiest (at least on a platonic level) to approach. For an object to become an artefact, it has to transcend the boundary of object/subject relationship and undergo a semiotically irreversible transformation; from being a rock, to being a hammer. The rock not only appropriates the function of a hammer, but likewise the idea of one, which, depending on how we look at it, is an eternal concept. The other two subcategories proposed for the articulation and definition of culture, both heavily rely on linguistic elements in the transmission of information from generation to generation. Often, this communication relies on spoken and/or written language, which implicates an exponentially evolving margin of error and corruption of the authentic message each time it is relayed. As mentioned in the very beginning, an artefact is an object purposely and consciously created by a person to fulfil a specific purpose within a given culture, at a given time - something which contemporary science and sociology can employ in their research and understanding of historical consensus.

Over the last decades, parallel to the rapid evolution of software development, a new definition of the artefact has been introduced; as a tangible by-product, or error, occurring as the result of the computation of data. The sense of artefacts as digital by-products is similar to the use of the term ‘Artefact’ in the applied sciences, where it refers to something that arises from the process in hand rather than the issue itself. In the theories of natural science and signal processing, an artefact is ‘any error in the perception or representation of information, introduced by the involved equipment or technique(s).’ A compression artefact is arguably the most common artefact we encounter in our daily lives (much more so, than, say a Byzantine tool at the National Museum), which is a noticeable distortion of media (including images, audio, and video) caused by the application of lossy compression.

Lossy data compression involves discarding some of the media's data so that it becomes simplified enough for storage within a desired virtual space or for it to be transmitted within certain bandwidth limitations. In signal processing, particularly digital image processing, Artefacts appear as spurious signals near sharp transitions in a signal. Visually, they appear as bands or ‘ghosts' near edges; audibly, they appear as sonic echos.

When we, as a society, move towards a complete digitisation of all accumulated data and knowledge, does it not beg the question whether this ‘new’ artefact, or glitch/error, as we presently call it, will be a defining subcategory of the future in the theoretical construction and dissimilation of culture? Attempts to map the evolution of language and semantics will forever fall prey to the limitations of self-articulation (we can only describe language with the words it provides), and is as such incapable of holistically asserting any epistemological truth, which is why we tend towards an affinity for artefacts in our quest for authenticity and existential understanding of origin and direction - as opposed to the written word. However, when these artefacts are not solely produced by the human intuition and the human hand, but are in fact the by-products of rogue and overloaded algorithms, it somewhat short-circuits the romantic notion that human action and ingenuity stands as the primary agents of our time.

Recently, scientists have exclaimed that we have now officially entered the age of The Anthropocene; A geological epoch in which the activity of man is the dominant influence of environment, climate, etc. However, one might suggest, as with all historical ideologies and narratives, that the identification of the anthropogenic era has emerged retrospectively, and what we are currently living through could appropriately be referred to as The Algopocene. ‘Algo’ carrying the double meaning of both being the abbreviation used in a variety of coding languages for algorithm, as well as álgos being the greek word for ‘pain’ and on an expanded spectrum ‘anxiety’. The Age of Anxiety.

Anxiety being a diffuse, objectless, future-oriented variation of fear; a (de)motivating factor of human actions, that will have profound social, cultural, geopolitical and economical impact on our society, likely on par with the consequences we have attributed to the anthropogenic. It will determine elections, policies, ethics and identity for years to come, it will lay bare a capitalist structure where the continual production and consumption of goods determines priorities of public health and welfare. An anxious population will be kept in check and line by cliff-hanger negotiations of congressional support-schemes or ever-postponed prospects of international trades deal and future custom restrictions, ensuring that final decisions and proclamations are solely made on a basis that more suspense and uncertainty will unavoidably follow. Anxiety, being at once personal, yet collective and at the same time abundantly universal, crosses the threshold of what we have started to refer to as ‘hyperobjects’ - entities of such vast temporal, spacial and existential dimension that they defeat traditional ideas of what constitutes any articulated object or phenomenon. A hyperobject cannot be defined nor indicated by any single sensory experience of reality, its accessibility is most often solely permitted through data and analysis, and its visceral sensation is somewhat analogous to an uncanny interruption of the physical real.

Our anxieties are embodied and amplified by a relentless image culture that indirectly lends shapes and forms to more immediate fears; something we can directly engage with, as opposed to the nature of anxiety. Anxiety takes no form, it poses no direct or immediate threat to organic or material matter (however, it enables this threat), it does not ‘steal our job’, ‘disrespect our God’ nor ‘violate our borders’ - it is, as a hyperobject, beyond conventional classification; it is ambiguously spiritual yet explicitly concrete. It is as detrimental, pertinent and terminal in its presence as any future religion or messianic deity could possible be or become.

Algopolis, 2020 (Detail)

Reclaimed heat sinks on welded steel table

100 x 200 x 115 cm

Algopolis, 2020 (Detail)

Reclaimed heat sinks on welded steel table

100 x 200 x 115 cm

Algopolis, 2020 (Detail)

Reclaimed heat sinks on welded steel table

100 x 200 x 115 cm

Untitled_CellF1, 2020

Malfunctioned and anodised solar cells in welded steel frame

200 x 200 cm

Untitled_CellF1, 2020

Malfunctioned and anodised solar cells in welded steel frame

200 x 200 cm

Untitled_Artefact_1-3, 2020

Rejected and malfunctioned silicon semiconductor wafers on mount

30 cm diameter each

Silicon Semiconductor Wafers

Almost all production of today's electronic technology involves the use of silicon semiconductors. The functions of which includes the amplification of signals and energy conversion, the most important aspect being the integrated circuit (IC), which are essential in the development and use of computers, smartphones, medical and military hardware etc. There are approximately 68 million square meters of silicon semiconductors shipped around the world each year, however it is one of these few obscure things that are ever present, yet very rarely come in direct contact with - making Silicon Valley a rather befitting alias. Besides including some of largest companies in the world, particularly in Taiwan, China and Japan, the semiconductor industry is the third largest manufacturing sector in the US economy with the unique feature of having approximately 25% of its combined budget devoted solely towards research and development. This gives a notion of the projected importance of these devices in the future as we move towards an epoch of increasingly advanced and complex tasks performed by tech. Due to their widespread application in almost all industries, the companies that manufacture and test these are according to marketwatch.com, The Economist and CNBC Trading considered, albeit somewhat volatile, reliant indicators of the health of the overall global economy.

Silicon [Si-14] is a plentiful natural and non-metallic element of the carbon-family and makes up 27.7% of the earth’s crust, only surpassed by oxygen. It has the unique property of conducting energy under some conditions and insulating under others, while being resistant to very high temperatures and currents. The inherent properties of Silicon can be modified through introducing impurities (so-called doping) Through a variety of chemical and mechanical processes, allowing for increased conductivity and maximised control. These characteristics make it an ideal material for making transistors that amplifies and conveys electronic signals.

A symbolic comparison of the semi-conductor’s role in a computer would be to that of the nervous system of the body. It regulates and controls impulses and distributes the necessary amounts of data and energy to the appropriate sectors of a much larger and completely interdependent system

The colours and composition of these particular wafers are all due to glitches and errors in the manufacturing process, what in computational science is known as artefacts.

Untitled_Artefact_5, 2020

Rejected and malfunctioned silicon semiconductor wafers on mount

30 cm diameter each

Untitled_Artefact_8, 2020

Rejected and malfunctioned silicon semiconductor wafers on mount

30 cm diameter each

Untitled_Artefact_9, 2020

Rejected and malfunctioned silicon semiconductor wafers on mount

30 cm diameter

Untitled_Artefact_5-6, 2020

Rejected and malfunctioned silicon semiconductor wafers on mount

30 cm diameter each

Untitled_Artefact_9-11, 2020

Rejected and malfunctioned silicon semiconductor wafers on mount

30 cm diameter each

Untitled_Artefact_12-14, 2020

Rejected and malfunctioned silicon semiconductor wafers on mount

30 cm diameter each

--------------------------------------------------

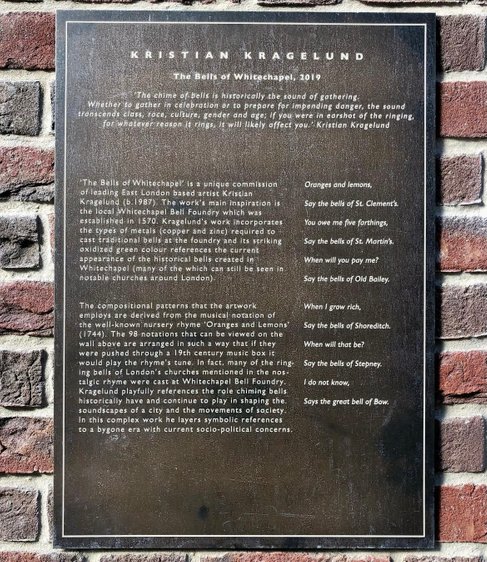

The Bells of Whitechapel, 2020

The Bells of Whitechape, Permanent Public Commission, Whitechapel, London, UK

The Bells of Whitechapel is a permament public sculpture developed in response to the rich history of manufacturing in the Whitechapel area of London's Eastend and particularly considering The Whitechapel Bell Foundry as a point of departure.

The Whitechapel Bell Foundry was heralded as UK’s oldest manufacturing company dating back to 1570, and its recent closure has been widely contested and condemned as emblematic of a corrosion of the identity and sensibilities of our city and its communities at the heart of an area that is known for its cultural and ethnical diversity.

Each bell foundry around the world has its own unique alloy of copper and zinc for their casting process - copper for resonance and zinc for strength - resulting in distinctive qualities, each exclusive to the specific foundry. By working closely with former casters from the Whitechapel foundry we managed to reproduce and cast their particular alloy into large sheets. These sheets were cut, folded and welded in the precise dimensions of the bricks of the wall where the work was to be mounted.

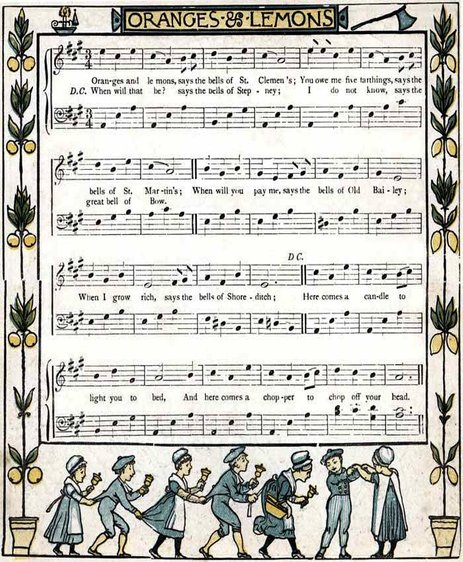

The final arrangements of the alloy bricks is in reference to the music-box notation of an old British nursery rhyme ‘Oranges and Lemons’ in which each verse refers to a different bell/church tower in London, all of which had their bells cast in Whitechapel.

Historically the chime of bells were the sound of gathering. Whether to gather in celebration or to prepare for an imminent threat, the sound would transcended class, race, culture, gender and age. If you were within earshot of the bells, it would likely affect you.

This work was developed under the long shadow of a conservative government and the perpetual Brexit deadlock. This was a period in which I found the UK to be politically, culturally and socially fractured, and in many ways at an ideological crossroad. However, as a result of the extraordinary situations of political turmoil we have collectively lived through, there seems to be a growing sense of community and compassion across most spectrums of society and one can only hope that this will last and manifest into a reality of compassion and care instead of our current one of disparity and division.

The Bells of Whitechapel, 2020

--------------------------------------------------

The Bells of Whitechapel, 2020

The Bells of Whitechapel, 2020

Original lyrics for Oranges & Lemons with illustrations by Walter Crane (1845 - 1915)

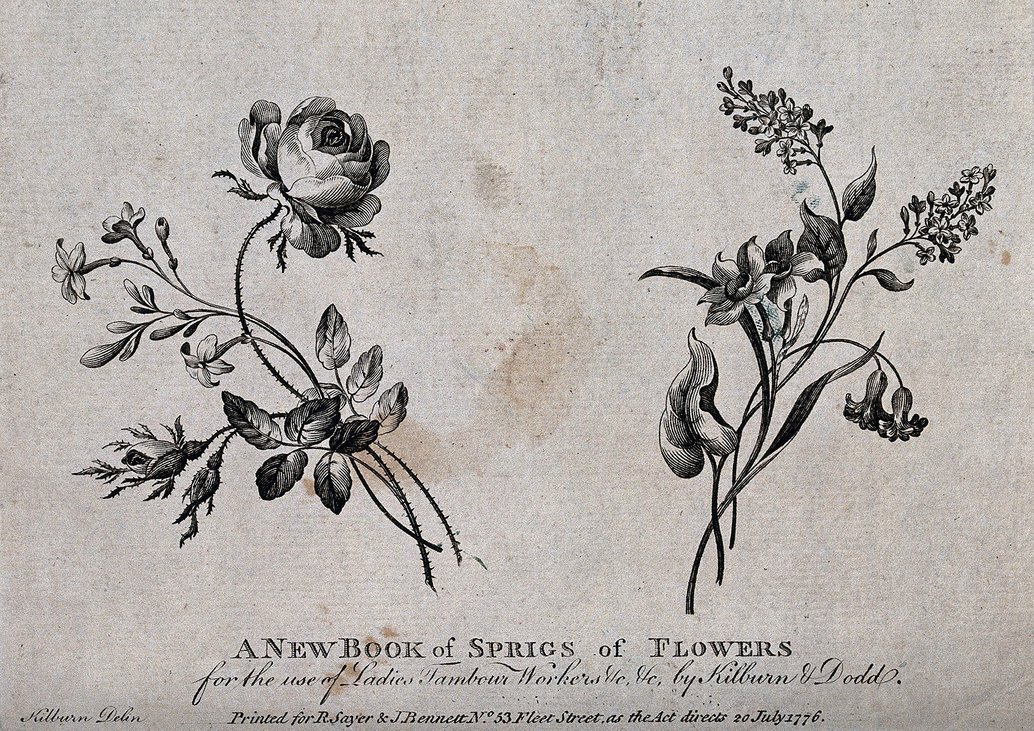

Flower Etching by W. Killburn, 1772 (source image)

Study of Artificial Flower after W. Killburn 1772, I, II

Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University, New York, US

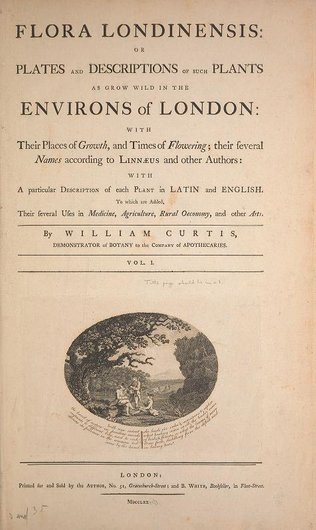

In 1777 a book called Flora Londinensis was published by the botanist William Curtis. It included several intricate copper stitchings by the foremost botanical artists of the time, and its stated purpose was to catalog the natural flora in a ten mile radius of London; to document the “rich and beautiful” nature around the capital of The British Empire.

As imagined, the majority of the flowers depicted in the volume were non-native to England as they had been imported, often by chance and accident, by sailors and soldiers returning home from the far corners of The Empire.

Due to the overwhelming public interest in the publication outside of its intended scientific circles, one of the illustrators of the volume, a W. Killburn, started reproducing his illustrations as decorative tapestries and wallpapers for the residences of the aristocracy and ruling class. Kilburn soon realised the artistic and financial potential of these reproductions and therefor petitioned The Crown that the work would be licensed and only re-producible under his authority. Though the request was ultimately denied, Kilburn’s action can be considered one of the first instances of an artist attempting to legally copyright their work.

However, when viewed through the critical lens of history, Killburn’s legal request could merely be considered an extension of the violent colonial conquest of The British Empire and the cultural apparatus that sustained it — by claiming legal and artistic ownership of the ‘rich and beautiful’ natural environments of occupied nations and territories by the very institution through which he applied for formal control and ownership of not only the illustrations, but likewise of the natural forms depicted in them. The flowers in these two paintings are 2023 reproductions of W. Killburn’s 1772 reproductions, and are currently on display at Wallarch Gallery at Columbia University under the titles ‘Study of Artificial Flower after W. Killburn 1772, I, II’

The original etching can be seen at The Wellcome Collection in London, UK.

Study of Artificial Flower after W. Killburn 1772, I, II, 2023

Oil, enamel, fibreglas and resin on canvas in welded artist frame

140 x 90 cm each

Flora Londinensis by William Curtis, 1777

Study of Artificial Flower after W. Killburn 1772, I, 2023

Oil, enamel, fibreglas and resin on canvas in welded artist frame

140 x 90 cm

--------------------------------------------------

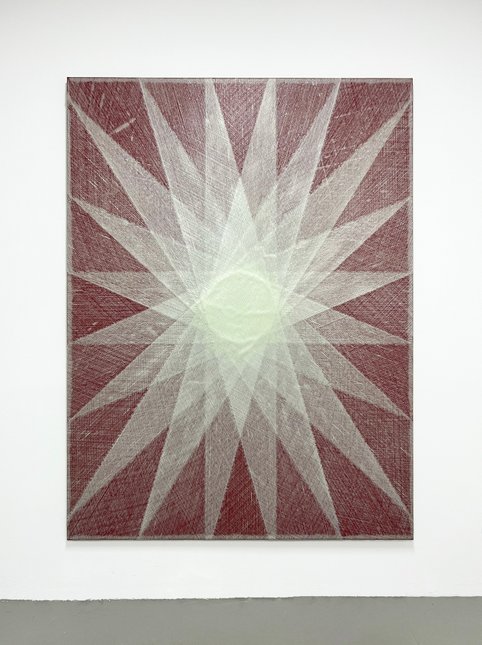

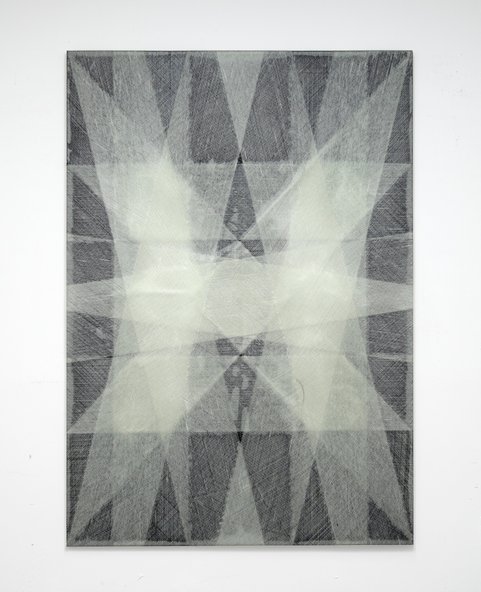

Untitled_MB_LO04, 2023

Oil, fibreglass and resin on canvas

200 x 150 cm

Untitled_MB_LO06, 2023

Oil, fibreglass and resin on canvas

200 x 140 cm

Untitled_MB_LO01, 2023

Oil, fibreglass and resin on canvas

200 x 140 cm

Untitled_MB_m01, 2021

Oil, fibreglass and resin on canvas

180 x 110 cm

Study of Artificial Flower after W. Killburn 1772, II, 2023

Oil, enamel, fibreglas and resin on canvas in welded artist frame

140 x 90 cm

Mach Bands

Mach Bands refers to an illusion where a band of adjacent gradients will visually appear to be lighter or darker than they actually are by triggering an edge-detection response in the optical nerve.

The phenomena is named after the Austrian physicist Ernst Mach (1838-1916) who is known and recognised for his work in optics, mechanics, wave dynamics as well as notable advances in the (then) theoretical field of supersonic travel.

The concept of Mach Bands is applicable in several different scientific fields, often to vastly different, and sometimes outright contradictory effect.

In nature, it helps boost the perception of an objects periphery, making it possible for an animal to detect the edge of an approaching threat from outside their general field of vision; one that might otherwise not be have been noticed until it it was too late. (Anticipatory)

However, in modern medical science this has paradoxically been attributed as a source of diagnostic error in radiology, where damaged tissue gets overlooked and misdiagnosed - potentially with fatal results. (Delayed)

Furthermore, in rendering computer graphics of virtual environments, for example in gaming or for CGI reliant movies, the Mach effect is used as a technical mean in smoothing or separating distinctive surfaces. This is done to create an enhanced experience of the virtual, where an artificial space becomes as interchangeable as possible from reality. (Concurrent)

The study of Mach Bands can, in my opinion, offer perspective and alternative understandings of the body in relation to space - and ultimately have the potential to reconfigure binary assumptions of representation and perception.

Untitled_MB_LO05, 2023

Oil, fibreglass and resin on canvas

200 x 140 cm

Untitled_MB_m03-04, 2021

Oil, fibreglass and resin on canvas

180 x 110 cm each

Untitled_MB_m02, 2021

Oil, fibreglass and resin on canvas

180 x 110 cm

Untitled_MB_s01, 2021

Oil, fibreglass and resin on canvas

76 x 56 cm

--------------------------------------------------

Untitled_MB_s02, 2021

Oil, fibreglass and resin on canvas

76 x 56 cm

Untitled_MB_s03, 2021

Oil, fibreglass and resin on canvas

76 x 56 cm

Untitled_CellX1-3, 2019

Anodised first generation solar cells mounted on aluminium in artist frame

107 x 75 cm each

A ‘Cellular Automaton’ (CA) is a structure studied in computer science, mathematics, physics, complexity science, theoretical biology and microstructure modelling.

The concept was first articulated by two professors in 1940s, one studying the growth and self-replication of crystals, another working on the problem of self-replicating systems; initially founded on the notion of one robot building another. The latter coming to realise the complexity of building a self-replicating robot and the great cost of providing the initial robot with the parts for which to build the replica, eventually causing the two to combine their fields of study.

Together they created a method for calculating liquid motion in the late 1950s, which was the first system of Cellular Automaton. The driving concept of the method was to consider a liquid as a group of discrete units and calculate the motion of each based on its neighbours' behaviours.

In 1970 a mathematician devised ‘The Game of Life’ based on the principles of cellular automaton.

The game is a zero-player game, meaning that its evolution is determined by its initial state, requiring no further input. One interacts with the Game of Life by creating an initial configuration and observing how it evolves.

The rules are as follows:

1.Any live cell with fewer than two live neighbours dies, as if caused by underpopulation.

2.Any live cell with two or three live neighbours lives on to the next generation.

3.Any live cell with more than three live neighbours dies, as if by overpopulation.

4.Any dead cell with exactly three live neighbours becomes a live cell, as if by reproduction.

‘Game of Life’ is undecidable, which means that given an initial pattern and a later pattern, no such algorithm exists that can tell whether the later pattern is ever going to appear; whether a given program will finish running or continue to run forever from an initial input.

Despite its simplicity, the system achieves an impressive diversity of behaviour, fluctuating between apparent randomness and order. In chaos theory this transition zone between the two regimes is known as the ‘Edge of Chaos’, a region of bounded instability that engenders a constant dynamic interplay between order and disorder.

Adaptation plays a vital role for all living organisms and mathematical systems. All of them are constantly changing their inner properties to better fit in the current environment. The most important instruments for the adaptation are the self-adjusting parameters inherent for many natural systems. The prominent feature of systems with self-adjusting parameters, (i.e. global financial markets, nation-states) is an ability to avoid chaos, yet teeter on the edge of it to optimise output.The name for this phenomenon is "Adaptation to the Edge of Chaos”.

Adaptation to the edge of chaos refers to the idea that many complex adaptive systems seem to intuitively evolve toward a regime near the boundary between chaos and order, which, in physics and politics have shown that edge of chaos is the optimal settings for control of a system.

Untitled_Cell1_1-12, 2019-2023

Anodised first generation solar cells mounted on aluminium in artist frame

77 x 50 cm each

Untitled_Cell1-12, 2019-2023

Anodised first generation solar cells mounted on aluminium in artist frame

137 x 92 cm each

‘Pattern theory’ is an artificial intelligence formalism used to describe knowledge of the world as ‘patterns’. Unlike other AI paradigms, it does not begin by prescribing algorithms to recognise and classify complex problems, rather, it defines an initial vocabulary to articulate and organise repetitive concepts in concise patterns.

In computational theory, a pattern can be considered a less specific version of an algorithm. Whilst an algorithm might focus on a particular programming task, a pattern has the potential to consider challenges beyond a singular function and into areas such as reducing defect rates, increasing maintainability of code, or allowing large teams to work more effectively together.

Pattern based theory is widely applied in speech and facial recognition, as well as in the uncanny invention of ‘Generative Adversarial Networks’ (GAN) which allows for so-called human-image-synthesis, i.e. deepfake videos, images and consequentially, news.

In software development, the reciprocal notion to the logic of pattern theory is the concept of ‘anti-patterns’. It can be characterised as the application of a commonly used process, structure, pattern or action, that despite appearing to be an appropriate and effective solution to a given problem, eventually yields more negative consequences than positive ones.

Below is a simple pattern-based AI generated fairytale; initially providing a (somewhat) conventional narrative structure, in which the internal logic gradually starts to collapse, progressively rendering itself cyclical and ultimately becomes contextually nonsensical. Thus affirming the sentiment of anti-patterns and the inherent complications and traps of GAN and other pattern-based AI systems.

The boy who owned the small cottage went to the deep forest

The prince walked to the lake

The girl walked to the lake and the princess went to the lake

The pretty prince walked to the dark forest

The evil evil prince walked to the lake

The prince walked to the dark forest and the prince walked to a forest and the princess who lived in some big small big cottage who owned the small big small house went to a forest